Niall Ferguson cautioned that empires unravel from within when the institutions meant to sustain them weaken under the strain of their own inefficacy, eroding public trust as they cease to fulfill their intended purpose. The American empire has not yet disintegrated, but its foundations have been critically undermined. Once destabilization reaches a tipping point, the descent is swift and irreversible. Watching the news, it certainly appears as though we’ve crossed the Rubicon.

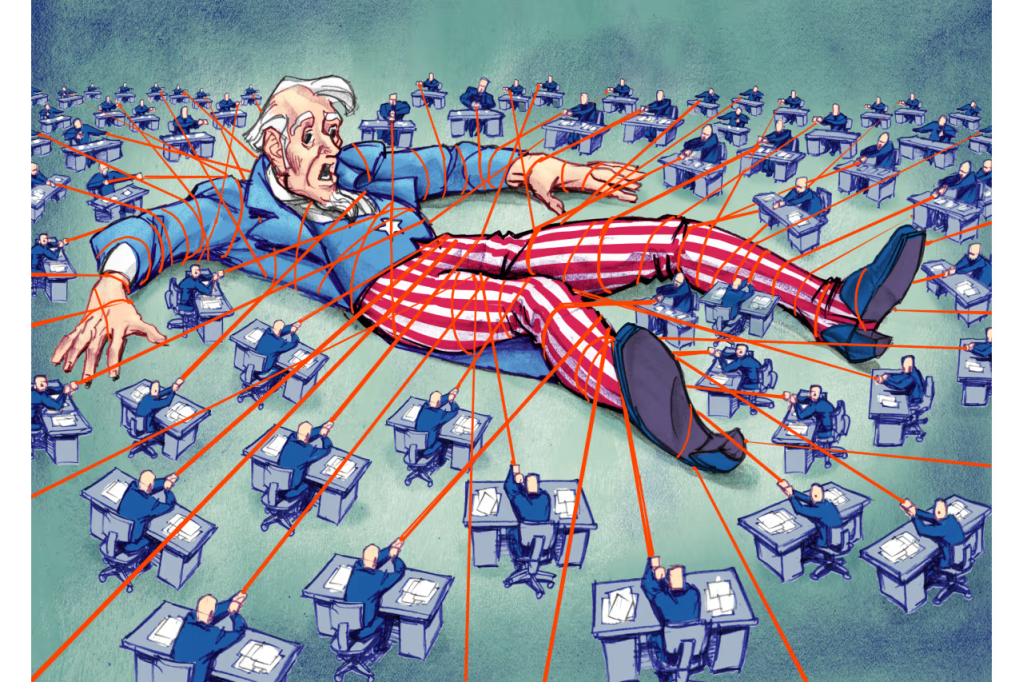

The Deep State, ostensibly the mechanism that should have mitigated such an implosion, was and continues to be systematically vilified and dismantled. The very apparatus responsible for insulating democratic governance from impulsive political excess was delegitimized by the very elites it was designed to serve. The power elite failed to recognize the peril of abandoning their stabilizing mechanisms.

Rather than act as the shadowy, conspiratorial force caricatured in populist rhetoric, the Deep State has historically functioned as a necessary ballast, preserving institutional integrity amid fluctuating political landscapes. However, its failure to navigate a treacherous political realignment—and its inability to circumvent the populist revolt against expertise and bureaucratic governance—has left American democracy increasingly vulnerable to collapse. In the absence of stable institutions, governance defaults to personality-driven rule, where spectacle and gut instinct replace deliberation and strategy.

The postwar American state was structured around an expanding bureaucratic and security apparatus that safeguarded economic stability, strategic hegemony, and social order. From the 1940s to the early 2000s, institutional growth coincided with the expansion of the middle class and the maintenance of a delicate equilibrium between economic elites and the general populace.

However, as institutions ossified, their fundamental purpose—protecting the middle class from the unrestrained ambitions of the ruling class and restraining elite overreach—was abandoned. The 2008 financial crisis revealed this failure with devastating clarity: banks were rescued while working-class homeowners were left to absorb the collapse. The Iraq War further discredited institutional legitimacy, exposing the military-industrial complex’s predatory interests as contractors reaped fortunes while veterans returned to shattered lives.

Globalization, as much maligned as the Deep State, was executed without guardrails—without mechanisms that could have balanced local economic strength, national security, and long-term stability. Instead of serving as a model for inclusive economic expansion, it was weaponized by corporate interests, enabling a mushrooming class of new billionaires to maximize profit at the expense of national resilience.

The expansion of global markets created unparalleled opportunities for capital accumulation, allowing corporate giants to optimize production through the exploitation of cheap labor while expanding their consumer base to a global population of eight billion. This was not globalization’s failure, but rather the failure of institutions to regulate its trajectory—to ensure that economic expansion did not result in unchecked wealth concentration and the erosion of domestic economic stability.

The billionaires and multinational corporations that emerged from this transformation did so by systematically reducing production costs through labor arbitrage while maintaining high-margin profitability in the wealthiest consumer markets. The institutions that once constrained corporate excess were no longer equipped to mediate the balance between capital and labor; instead, they facilitated the very conditions that entrenched economic disparity.

Similarly, the Deep State is neither benevolent nor malevolent; nor can it be dismissed as “anti-democratic” if it works to safeguard a democratic republic. Considering that it is an amalgamation of bureaucratic frameworks, intelligence agencies, regulatory bodies, and financial institutions that collectively function as the administrative machinery of governance, it is not an agent of authoritarian control but rather a structural necessity, ensuring policy continuity beyond electoral volatility. Democracy requires this.

History provides clear precedents for what happens when institutional stability collapses. The Roman Republic unraveled not solely because of Julius Caesar’s ambition but because the Senate—once the state’s bureaucratic ballast—lost its ability to constrain executive overreach, allowing populist demagoguery to replace deliberative governance. The Ottoman Empire did not simply fall to external pressures; its ruling bureaucracy weakened while the Janissary corps, originally an elite military force loyal to the state, transformed into a self-serving political faction, resisting reform and prioritizing its own privileges over imperial stability. The Qing Dynasty collapsed when its bureaucracy—once a model of Confucian meritocracy—failed to modernize in response to industrial and imperialist pressures, leading to economic stagnation and foreign encroachment.

Each of these cases underscores the same principle: when the administrative institutions designed to balance power falter, the door opens for opportunists, who, instead of strengthening the system, accelerate its collapse.

We are living in an era where vitalism is holding sway over determined managerialism. Popular psychology elevates manifestation, energy, and intuitive impulse over deliberate, systematic action. Self-help gurus preach that intention shapes reality, that vision alone bends the arc of events. It is no wonder, then, that political leadership has begun to mirror this trend—governing less through strategic calculation and institutional rigor and more through charisma, instinct, and performance.

To be sure, human limitations require that iterative deliberation be cut off at a certain point, and decisions must be made. The presence of urgency does not, however, justify the abandonment of rational process in favor of blind impulse. The political organism, much like the biological one, cannot survive on unregulated spontaneity alone.

This is where Iain McGilchrist’s theory of brain lateralization provides a useful lens. The right hemisphere, associated with intuition, emotion, and big-picture thinking, thrives on immediacy and gut feeling. The left hemisphere, by contrast, specializes in analysis, categorization, and procedural structuring—the very faculties necessary for sustained governance. In a functional system, these two domains are in balance, with the right hemisphere generating vision and the left implementing it.

But when vitalism dominates without an institutional counterweight, governance devolves into erratic decision-making, unmoored from structure, precedent, or strategic foresight. It is the political equivalent of governing from the right hemisphere without left-hemispheric constraints.

The United States, once a paragon of structured managerialism, is increasingly operating in this state of dysfunction, where policy is dictated by emotional reaction, spectacle, and the immediacy of the news cycle rather than by institutional continuity and long-term planning.

Historically, no enduring state has thrived under unchecked vitalism. Napoleon’s France, the Third Reich, and even Imperial Japan all relied heavily on emotional mobilization and ideological fervor, but each succumbed to the limits of unregulated ambition—overextension, internal instability, and the inability to manage power in the long term.

Lee Kuan Yew’s Singapore, by contrast, succeeded precisely because it recognized the necessity of institutional discipline. A strong state, like a strong mind, must balance intuition with structure, instinct with rational oversight.

If history has taught us anything, it is that once the guardrails are gone, they do not reappear on their own. The Power Elite who believe they can ride this storm without consequence are mistaken. The time for course correction is vanishing, and when the reckoning comes, it will not be evenly distributed.