On the Layers of Self and the Question of Destiny

David Brooks, in How to Know a Person, offers us a useful architecture of the self: four distinct layers that together compose a human being. The Presented Self, which the world sees — the curated, optimized exterior. The Inner Self, where conscience, memory, and character reside. The Suffering Self, which carries the weight of old wounds, shame, grief, and pain. And the Transcendent Self — the one that looks toward something larger, beyond, above; the aspirational gaze at one’s hopes and dreams.

Brooks introduces this model to help us see others in their fullness. He gives us a map for becoming the kind of person who can witness depth in someone else. But like all good models, it does more than it says. It invites repurposing.

And so we ask a question Brooks never poses — but which his framework illuminates:

Where should we dwell? In which layer do we find the shape of our becoming?

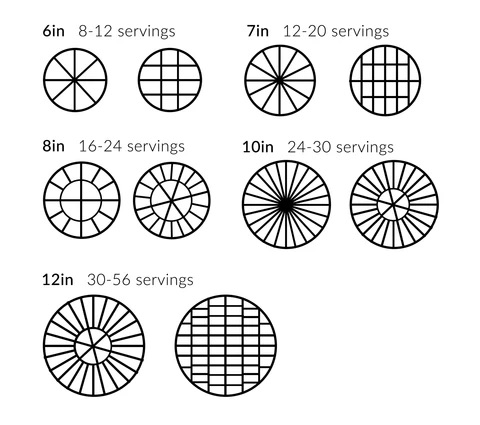

We make no metaphysical claims here — the self is no more four layers than a pizza is eight slices. You can slice the self a thousand different ways, each offering new insight. But Brooks’s divisions prove particularly helpful in answering the question we have posed.

To that end it helps to imagine the self not as a pizza or cake (excellent choices though they may be) to be consumed, but as a house to be lived in. Picture the house a child draws: two stories, a door in the center, four square windows, a triangle roof with a chimney. What you don’t see is the basement. Brooks’s model reveals this missed layer.

The Presented Self is your facade, the foyer and salon — where the neighbors wave, the packages arrive and formal guests make small talk.

The Inner Self is the study, the bedroom, the private places with books, mirrors, and unwitnessed time.

The Suffering Self is the basement — damp, hidden, still holding flood marks from old storms.

And the Transcendent Self is the rooftop — where you climb to see the stars and whisper toward the sky.

You are not one of these. You are all of them.

But that leads us to a deeper question.

Brooks wants us to see others more fully by exploring each of these layers of their persona and opening ourselves to being seen at each of these, in his telling, levels. But what if we turn our gaze inward and ask: where should we look? Not just in how we relate to others — but how we arrange our own time, energy, and attention.

Further, does the floor we live on determine the shape of our life?

Should we spend most of our time on the roof, aspiring? Should we strive for balance across all levels? Should we move seasonally, letting life tell us where to be?

This is the question that haunts the blueprint. Because it seems increasingly clear that the floor you inhabit most often becomes the gravitational center of your character — and perhaps even your destiny.

Live too long in the Presented Self, and you become a projection.

Live too long in the Inner Self, and you become a recluse.

Live too long in the Suffering Self, and you become a wound.

Live too long in the Transcendent Self, and you become a cloud.

And yet — perhaps some are called to dwell longer on one floor than another. The grieving must attend to the basement. The contemplative must fortify the roof. The young must learn to clean their rooms before they climb up on the roof.

So what’s the answer?

THREE THEORIES OF INHABITANCE

The Roof is Everything

One may posit that we should live mostly in the transcendent. That vision, meaning, and moral purpose should be our primary concern — the roof is where orientation happens. We should be standing in the present and looking forward.

But a roof without a house is a tarp. A gesture towards something that never got built – architecture without inhabitation.

Spend too much time manifesting abundance, and you become a billboard, not a being.

Balance is the Goal

Another possibility is that we are meant to circulate equally. Visit every room. Give no single space priority over the others. This is the ethic of integration.

But balance can become stasis. It risks imposing a symmetry that even nature does not observe.

The seasons cycle, yes — but no winter is the same as the last, no summer without its own drought or downpour.

A perfectly rationed life may be tidy, but is it natural?

Seasonality is Wisdom

A third path suggests movement by need. Some days demand the basement. Others call you to the roof. Some seasons require solitude. Others, performance or repair.

But seasonal living requires discernment. How do you know when it’s time to leave the basement? How do you know whether you’ve reached the rooftop or simply climbed a ladder to nowhere?

YOU ARE A HOUSE, NOT A FLOOR

One thing we can say for certain is that the modern obsession with “finding your authentic self” insofar as it assumes there is a single, goldenthreaded core waiting to be uncovered – is a false promise.

There is no single self, only rooms to be furnished and lived in — some better lit than others, some waiting to be opened.

You do not find yourself. You become habitable.

You are the one who climbs the stairs. Who checks for mold. Who opens the blinds. Who replaces the broken knob.

This is not selfactualization. This is maintenance. This is care.

THE QUESTION STAYS THE SAME

So, where should you dwell?

Should you aim for the roof? Balance the levels? Follow the seasons?

I have no fucking idea.

But perhaps your destiny lies not in the room you choose, but in the way you move between them.

Now put that in your pipe and smoke it.