Dissenting Opinion by Justice Thomas

I respectfully dissent.

The Court today reaffirms the constitutionality of a system so bloated with unaccountable power that its distance from the Founding compact is no longer one of degree, but of kind. While the Constitution was crafted to establish a federal government of limited and enumerated powers, our modern administrative state operates by a different logic entirely: one of delegation without accountability, rulemaking without representation, and enforcement without restraint.

The Petitioners do not ask us to overturn democracy. They ask us to recall the design. The majority responds by sanctifying a machinery that would have alarmed the very men whose names it invokes.

I. The Constitution Was Meant to Secure Natural Rights, Not to Replace Them

At the center of our constitutional order is the principle that government exists to secure the natural rights of its citizens. That truth, plainly stated in the Declaration of Independence, animates the Constitution itself. It is not merely aspirational rhetoric. It is the foundational assumption that gives our legal order meaning.

When Congress enacts laws and empowers agencies to issue thousands of binding regulations that control how Americans build, farm, educate, and speak — regulations that no elected official drafts, and few citizens can comprehend — we must ask: is this still a government that secures liberty, or one that administers submission?

II. The Founders Could Not Foresee, But They Did Forbid

The majority concedes that the Founders could not have imagined the modern administrative state. Yet it insists their silence implies consent. I reject that inference.

The Constitution’s enumerated powers were meant as limits, not suggestions. Its structure — separation of powers, bicameralism, presentment — was designed to constrain power, not to license its redistribution. When Congress delegates vast legislative authority to executive agencies and insulates them from meaningful oversight, it evades the structure, and therefore violates the design.

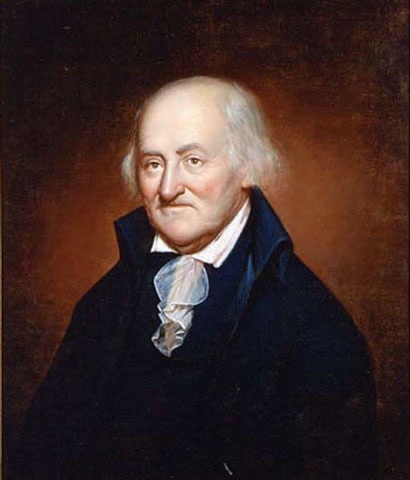

It is no answer to say that Hamilton oversaw customs houses. That is enforcement, not governance. Hamilton did not write rules governing speech, medicine, or wetlands. He executed laws — he did not create them.

III. Petitioners Are Not Revolutionaries. They Are Restorers.

The Court worries that Petitioners seek to disobey constitutional laws and undermine the rule of law. But the true lawbreakers are the institutions that now govern by proxy, presumption, and perpetuity. Petitioners ask only for protection from unlawful rulemaking — and the ability to defend themselves when coerced into compliance with measures that were never passed by any legislature and never subjected to public accountability.

Their proposal, the Madison Fund, is not a revolution. It is a legal defense fund — a recognition that power must sometimes be met with resistance in courtrooms, not only ballots. They do not reject the Constitution. They reject its evisceration.

IV. The Constitution is Not a Suicide Pact for Liberty

The majority offers a solemn moral aside, confessing that one day, should the law remain constitutional but become morally grotesque, it too might resist — but would do so “outside the system.” With respect, that formulation is precisely backward.

The system the Founders built was not meant to survive despite resistance to tyranny — it was meant to empower it.

When men of conscience disobey unjust laws, they do not renounce the Constitution. They uphold its purpose. Civil disobedience is not incompatible with constitutional fidelity when the laws in question were made outside of constitutional processes.

V. The People Are Sovereign — Not the Paper

Our allegiance is not to paper, but to principle. The Constitution is not sacred because of its ink. It is sacred because it rests on a deeper truth: that government is the servant, not the master. When that relationship is inverted — when laws are made by anonymous hands, and the people are taxed, fined, or silenced by mechanisms they did not consent to — then the Constitution is no longer operative in substance, however formally intact.

In such a moment, to say “obey first, petition later” is not fidelity. It is acquiescence.

VI. Conclusion

I do not glorify resistance. I do not dismiss the dangers of anarchy. But I also do not confuse order with legitimacy. A system that compels obedience while denying representation, that creates laws by bureaucratic alchemy, and that punishes the disobedient without due process, is not the republic our Founders envisioned.

The Petitioners stand on firm constitutional ground when they challenge that regime — and a firmer moral one when they refuse to fund it with their compliance.

I dissent.