My son K and I watched neurosurgeon Michael Egnor’s talk at the 2025 Dallas Conference on Science & Faith. It had been suggested to me by someone with whom I was discussing my sense that we were, as a species, on the verge of a major breakthrough in understanding consciousness.

In his talk Egnor argues, from surgical cases, that certain phenomena (viz. split-brain patients who can apparently compare stimuli shown separately to each hemisphere, and veridical-seeming details learned during near-death experiences (NDEs)) point beyond materialism to the existence of the soul.

Afterwards, K’s reply was disciplined: before we invoke immaterial causes, we should exhaust material ones especially in areas we don’t yet measure well.

His reply reminded me of myself, though at a slightly older age, once I had been “college-read” and comfortably installed in a materialist posture. At that time I was the one glibly cautioning that we must never reach beyond what matter could someday explain. My cousin T, a decade my senior, then pushed in the opposite direction, pointing to mysteries that seemed to demand more. We sparred endlessly. Now, years later, I find myself closer to his view than to my own youthful certainty and not because I have been convinced by the evidence but because, life. I wondered whether K, too, will someday make that migration.

Corpus Callosum

Classic callosotomy disrupts interhemispheric integration; yet not all unity vanishes. Patients sometimes display unified awareness (e.g., being shown different images to each hemisphere, and still able to compare them). For Egnor, this suggests something beyond neural hardware is integrating experience. He nominates the “soul.”

I cannot say that logically follows. Though inclined towards the positing of a non-material agent, I recognize that this is most likely born of several decades of life rubbing up against the mysterious and ineffable.

Egnor also references cases where patients with flat EEGs or who are under anesthesia report vivid visual and aural perceptions, often including verifiable details (like “seeing” events in the room). Since the brain appears inactive, he argues, apperception must come from a non-material source which in his estimation is seated in the soul.

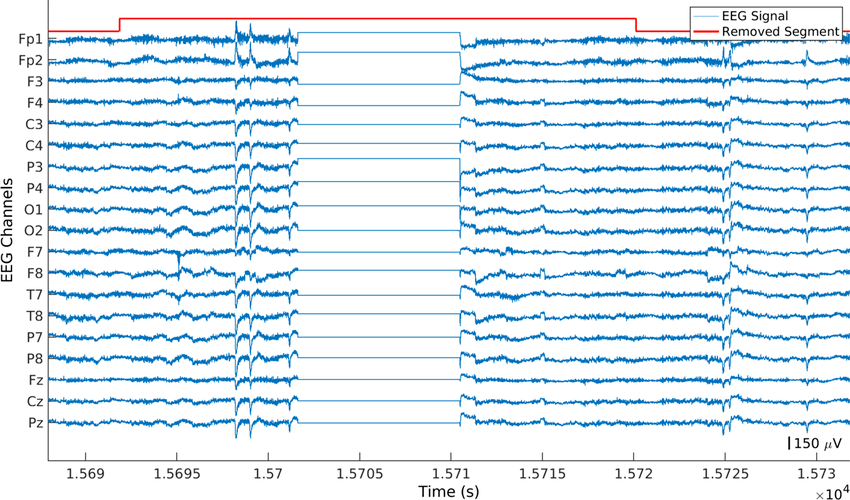

Flatlining an EEG seems definitive. But looked at more closely, it captures the limits of the probative value of the metrics adduced in these discussions.

A flat EEG indicates a lack of cortical scalp activity; it does not measure activity in brainstem or subcortical networks. Moreover, EEG is usually sampled intermittently in ICU or OR settings and not continuously with perfect resolution. Plus, the EEG has a detection floor. Small or desynchronized neural activity may be invisible but could still support fragments of consciousness or later memory formation.

Even if we could prove that there are no other material pathways that link the two hemispheres, as K suggested may be the case arguing science has yet to detect them, this only leaves us affirming that consciousness is not reducible to brain activity. It does not lead directly to the soul as Egnor argues.

Moreover a materialist could counter that these phenomenon are more readily explained through REM-intrusion, anoxia, neuromodulatory cascades, or confabulation, arguing there’s “nothing paranormal” about the core features.

The AWARE studies (led by Sam Parnia) tried to scientifically test for extrasensory perception by placing hidden visual targets in operating rooms and resuscitation areas. If patients truly left their bodies, they should report seeing them.

So far after thousands of cardiac arrests studied, only a handful of patients reported out-of-body experiences, and none reliably identified the hidden targets.

Still, the few veridical accounts remain intriguing and hard to fully explain leaving room for metaphysical conjecture.

Striking as these incidents may be, they are not probative of a non-material integrator by themselves.

While I would have normally agreed with K’s instincts and logic, I had already set a course towards Elysium. I couldn’t just turn the rudder and dock alongside his metaphysical prejudice. I had to sail on.

A Difference in Kind

If certainty remained out of reach, might we still discern which way the balance of evidence tilts, and how fully that evidence maps the terrain we are exploring?

K bit, offering that we were simply “smarter cavemen” playing with more complex implements.

But culture stores and improves thinking across generations; notebooks, code, networks, and now AI serve as cognitive repositories. That’s a qualitative transition in how minds operate.

Joseph Henrich calls this the collective brain. Our advances rest less on individual IQ and more on cultural inheritance and social learning spirals. It’s the reason Sapiens outlived the smarter Neanderthals. But the modern sapien knower is different in kind from his progenitor (a node in a distributed, instrumented cognition) rather than merely different in degree; as a consciousness that is.

We are not just homo sapien cavemen with better tools. We are fundamentally hybrid creatures, part biological and part technological. Our smartphones aren’t merely instruments we use; they have become extensions of our memory and reasoning. When I offload calculations to a computer or navigate by GPS, where does “I” end and the tool begin?

This extended cognition changes everything about how we understand consciousness itself. If minds routinely extend beyond skull boundaries, then the unity of consciousness that puzzles Egnor might not require a soul but rather reflects the distributed nature of mind across brain-body-world systems we haven’t learned to measure properly.

What’s Different from 2,000 Years Ago

Unlike the ancients, we can chart our ignorance. Physics knows its stress points (quantum gravity, dark matter/energy); biology flags origins of life and consciousness; mathematics lives with Gödelian limits and undecidables. This is not hand-waving. We can name the holes in the map and sometimes even bound them.

Ancient philosophers knew they didn’t understand lightning. We know exactly which aspects of quantum gravity remain mysterious. Our ignorance has become more educated, more structured, more productive.

Setting Boundaries

Two families of limits keep knowledge from being unbounded.

Descriptive bounds or limits of application set one form of boundary. The Standard Model explains three of nature’s four forces with uncanny precision, yet omits gravity altogether. Gravity, for its part, has its masterpiece in Einstein’s General Relativity: a theory tested to exquisite accuracy in planetary orbits and gravitational waves. But GR fails at the edges: it treats spacetime as smooth where quantum mechanics demands fluctuations, predicts singularities where no physical infinities should exist, and resists quantization in the language that unifies the other forces. Even joined with the Standard Model, GR cannot explain the dark sector that makes up most of the cosmos. The gap is not vague but precise: we know exactly where our two greatest maps must overlap, and there they dissolve into contradiction.

Physical constraints also operate to put a limit on knowledge. The universe has been shown to have a maximum storage budget. Jacob Bekenstein showed that any finite region of space can only hold a finite amount of information, proportional to the surface area of its boundary (not volume, due to black hole physics where matter collapses once critical density is reached). Meanwhile, Rolf Landauer proved that processing information always costs energy: whenever you erase or reset one bit, you must release heat because erasure destroys distinctions and increases entropy. Together, these principles mean that even with unlimited time and cleverness, our knowledge is bounded by the universe’s information budget, and every attempt to rework that information is metered by physics. This makes “endless knowledge” impossible in principle. We’re not just limited by our tools or lifespan; we’re limited by the fabric of reality itself.

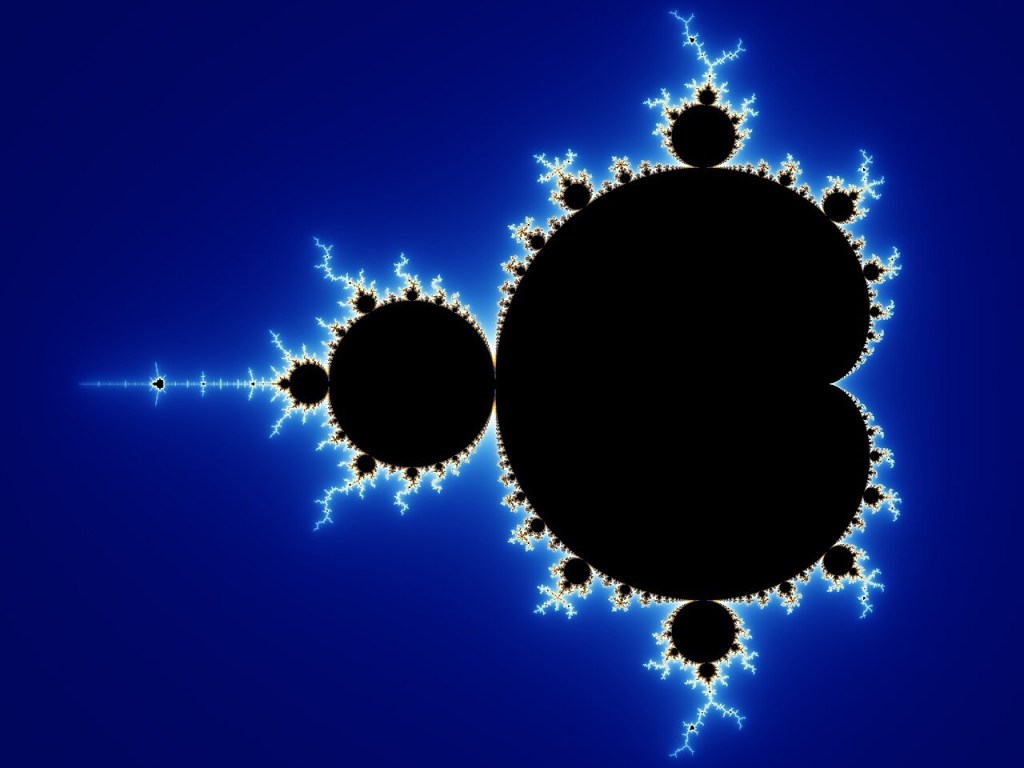

Yet, inside those limits, the detail is fractal: bounded in outline, inexhaustible in articulation. Within the universe’s information budget, the coastline keeps crenellating. New anomalies present themselves and new scales of explanation appear. That is “finite infinity” – a framed, but endlessly articulating, frontier.

Fractals are bounded sets with unending detail: finite area, effectively infinite perimeter. Mandelbrot’s set is the canonical image. That feels like the epistemic terrain we’re traversing: we’ve drawn a contour, but every increase in resolution reveals new structure.

Deductive Limits

The fractal metaphor gains depth when we consider how both deductive and inductive reasoning constrain our reach toward completeness, yet in complementary ways.

Deductive reasoning moves from premises to conclusions that must follow if the premises are true. Completeness in logic has a specific sense – a system is complete if every true statement within its domain can be proven from its axioms.

Gödel’s incompleteness theorem shattered the hope of absolute deductive closure. Any sufficiently rich formal system is either incomplete or inconsistent. Even in the realm of pure logic, there is no “final completeness.” We can have internally consistent systems, but there will always be truths beyond their reach.

Inductive Truth and Completeness

Induction generalizes from experience. The sun has risen every day, so it will rise tomorrow. Completeness in induction is never achievable, because inductive knowledge remains always provisional. The next observation could overturn the generalization.

Science is inductive at its core: each law or model is robust but not absolute. Newton led to Einstein led to quantum field theory led to…whatever the hell is going on right now. Completeness here would mean “closure of evidence”; having so much data that the pattern seems final. But as history shows, new instruments reveal new layers.

As Kuhn demonstrated, mature sciences can feel settled until anomalies nucleate demanding a paradigm shift. These remind us to treat closure with humility.

How They Intersect

Together, deduction and induction form a double guardrail:

- Deduction says even in perfect logic, completeness eludes you

- Induction says even in perfect observation, completeness eludes you

The fractal metaphor captures both: deduction provides the outline of the fractal (we know its rules) but Gödel tells us we’ll never exhaust the infinite detail. Induction provides the zooming in (every new instrument reveals fresh intricacy) but can never guarantee we’ve seen it all.

Completeness is blocked from both ends. Our knowledge has both logical boundaries and empirical horizons, and both keep receding as we approach them.

The Reflexivity Problem

But there’s something peculiar about applying the fractal metaphor to consciousness itself. When we study split-brain patients or cardiac arrest survivors, we’re using consciousness to investigate consciousness.

Minds examining minds.

This creates a strange loop that doesn’t exist when physicists study particles or biologists study cells.

The investigating subject and investigated object share the same ontological category, yet we pretend we can step outside the phenomenon to study it objectively.

This reflexivity may explain why consciousness remains so stubbornly mysterious. Every neural correlate we discover, every mechanism we map, leaves untouched the central question: why is there subjective experience at all? The hard problem persists not because our instruments lack resolution, but because the very act of measurement transforms the phenomenon we’re trying to capture.

Toward a Metaphysics of the Incomplete

The fractal structure of knowledge might reflect something fundamental about the relationship between finite minds and infinite reality. Perhaps the coastline keeps revealing new detail not because our instruments are inadequate, but because reality itself has this inexhaustible structure.

If so, then the soul question (and all the deep questions) aren’t problems to be solved but mysteries to be engaged. The dignity lies not in having final answers but in asking increasingly precise questions, in pushing material explanations to their limits while remaining open to what lies beyond those limits.

Science gives us real knowledge: the Standard Model works, DNA codes for proteins, brains correlate with minds. But it also gives us precise maps of ignorance. We know that dark energy comprises 68% of the universe but we just don’t know what it is. We can predict quantum probabilities to extraordinary precision and yet we can’t explain why measurement collapses wave functions.

This mapped ignorance represents genuine progress. The dignity lies not in claiming to have reached final answers, nor in claiming that no answers are possible, but in the quality of our questions and the precision of our ignorance.

The Generational Inheritance of Doubt

Watching K navigate these questions, I wonder whether the type of thinking each generation develops reflects the particular instabilities they witness during their formative years.

My generation came of age as Cold War binaries collapsed overnight in 1989, then encountered postmodernism’s systematic deconstruction of grand narratives and truth claims across academia and culture. We learned to distrust both sweeping political frameworks and overarching theoretical systems.

K’s generation witnessed different kinds of fragility: the 2008 financial crisis, climate change as constant backdrop, social media’s shattering of shared epistemic foundations, COVID’s rapid shifts in scientific consensus, AI’s resurrection of fundamental questions about mind and intelligence.

Does this produce different intellectual reflexes? Do we distrust metaphysical overreach because we saw both ideologies and master narratives crumble? Do they distrust claims about explanatory completeness because they’ve watched supposedly stable empirical systems prove fragile in real time?

Is this why K’s stance seems simultaneously more methodologically rigorous and more open in principle? Does growing up with paradigm shifts in real time create a different relationship to uncertainty than growing up with theoretical deconstruction?

On Aging and Disenchantment with Reductionism

Perhaps some of us soften toward non-reductionism as we approach our own reduction to particulate matter. But there’s another possibility: with time and experience, we develop an appreciation for mystery itself. Not mystery as ignorance to be dispelled, but mystery as a fundamental feature of how finite minds encounter infinite reality. We learn that some questions deepen rather than resolve as we investigate them more carefully and that this deepening is itself an elevated form of communing with knowledge.

Coda

We started with a neurosurgeon’s claim about the soul and ended with a coastline. The argument I would have wanted to put forth is this:

We, as knowers, changed in kind through cumulative culture and extended cognition; our minds are partially outside our heads.

Our best sciences map their own incompleteness (dark sector; gravity outside the Standard Model), and fundamental physics bounds what any finite agent can know or compute.

Therefore, “completeness” is fractal: the outline can be stable even as its edge is endlessly elaborated.

The conversation continues, as it should. The questions remain open, as they must. And perhaps that openness itself (the willingness to sail toward Elysium while charting the coastline with ever-greater precision) is the most honest stance we can take toward the deepest mysteries.

In the end, the fractal metaphor suggests that knowledge grows not by filling in blanks but by discovering new kinds of blanks to fill. Each resolution reveals new puzzles. Each answer generates new questions. This isn’t a bug in the system of knowledge, it’s a feature. And if consciousness remains mysterious after centuries of investigation, that might tell us something profound not about the limits of science, but about the nature of mystery itself.

Some coastlines might be worth exploring precisely because they never run out of new territory to map.