I find myself in constant awe of human creativity. Human creativity in its ordinary form, beyond the masterpieces, the unceasing churn of fonts, gadgets, fabrics, toys and tools, gushing into existence in such voluminous torrents the mind short-circuits to infinity.

Unless you are a fanatic minimalist just have a look about your house. If you are, walk out into the world (if you live in isolation, you’ll need to wander towards more inhabited areas) and just try and count the number of human creations around you. Those “objects” are the tip of an iceberg that also includes an entire value chain overpopulated by stuff made by human beings.

This fascination underlies an affinity I’ve always had for exploring human instruments and basking in the overwhelm that arises from contemplating the amount of time, attention and energy that was expended, in the aggregate, to bring these things into their multifaceted existence.

Consider the lowly tobacco pipe.

It is, in essence, but a bowl to burn tobacco connected to a tube for drawing up the smoke. But around this simple mechanism humans have spun a dizzying throng of innovations and variations.

Simple communal clay pipes eventually yielded to wooden ones, with briar emerging as the most suitable, especially the Algerian variety, persistently prized for its cool, dry smoke. Meerschaum, carved from the hills near Eskişehir in Turkey, appeared next to provide a neutral vessel for purists seeking the clarity of clay but with the resilience of stone.

When material considerations are set aside, pipe makers experiment with form.

Attention shifts to how a pipe should be shaped, how the bowl should sit in the hand, how the stem should meet the mouth, how the draft hole should align with the chamber.

Every choice matters from the angle of the drilling, the diameter of the airway, the taper of the stem, the bend or straightness of the shank. Small adjustments could turn a wet, gurgling pipe into a cool dry draw.

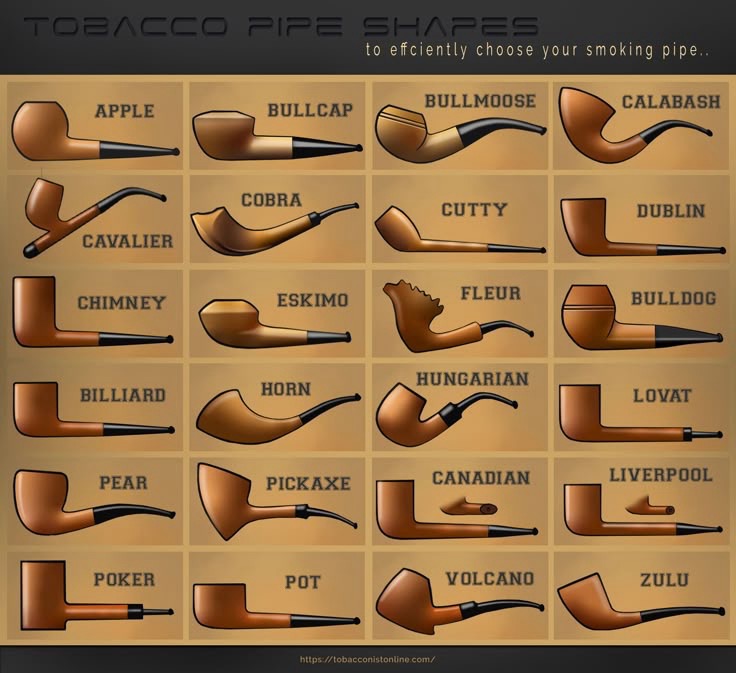

From these accumulated experiments phyla of standardized shapes emerged: the billiard, the bulldog, the Dublin, the Zulu, the prince, the author.

Names that sound almost mythological now, yet each is simply a settled solution to the same basic problem – how to burn leaf and draw smoke comfortably, predictably, and pleasurably.

The pipe is a case study in how creativity operates, within constraint, to produce the enduring forms of instruments.

Human anatomy exerts its own quiet authority here.

The hand wants balance. The jaw wants lightness. The lips want a stem neither too thick nor too thin. The eye wants proportions that feel inevitable. And everyone has their druthers. And today’s will gave way to tomorrow’s.

Even the most radical artisan shapes orbit these constraints; innovation pushes the boundary but rarely escapes the gravitational pull of what has worked for centuries.

Airflow, that invisible lifeblood of the smoke, became the hidden province of mastery.

A well-cut slot, a tenon properly tapered to minute tolerances, a draft hole perfectly centered at the bowl’s base, these are the invisible details that distinguish a masterpiece from a merely functional pipe.

It is remarkable how much human ingenuity has been spent perfecting something so simple: a bowl connected to a tube. And we haven’t even gotten to the different varietals of the tobacco plant, the treatment and curing methods, the casings, cuts and blends.

This precision of focus is continuously applied across every domain to challenges imperceptible to most, yielding refinements discernable by only a few.

Pipe innovation cannot be discussed without mentioning the reverse calabash, the tourbillon of the pipe world; dubious in net impact yet admired for the ingenuity of the premise.

For centuries, pipe design advanced through subtle refinements like better drilling, better stems and overall better proportions, but the fundamentals stayed intact. Then came the idea that the airway itself could become a chamber, that smoke could be given a moment to expand and cool before reaching the mouth.

A second chamber, hidden within the shank, functioning as a pressure buffer.

Nothing changes in the ritual: leaf in bowl, flame to leaf, breath to stem.

And yet everything changes in the experience. At least that is the intent and promise.

It is a reminder that innovation in long-mature traditions rarely comes from rewriting the rules. It comes from reimagining an invisible domain – airflow, pressure, gravity – while leaving the rest of the process intact. The anatomy may remain the same, bowl, shank and stem, but inside the walls something radical is happening.

Even though sales figures today project growth, I am fairly certain that sightings of lit pipes in the wild are rarer than the ring of a public payphone. Nevertheless, there are thousands of pipes still being made today, many by hand, trading for several hundred dollars.

It is a strange paradox: an instrument vanishing from daily life, yet flourishing in the hands of makers who still coax new possibilities from it. Rarity has not diminished the pipe’s hold on creative efforts. If anything, it has sharpened the question of what a pipe should be in a domain inhabited by aficionados.

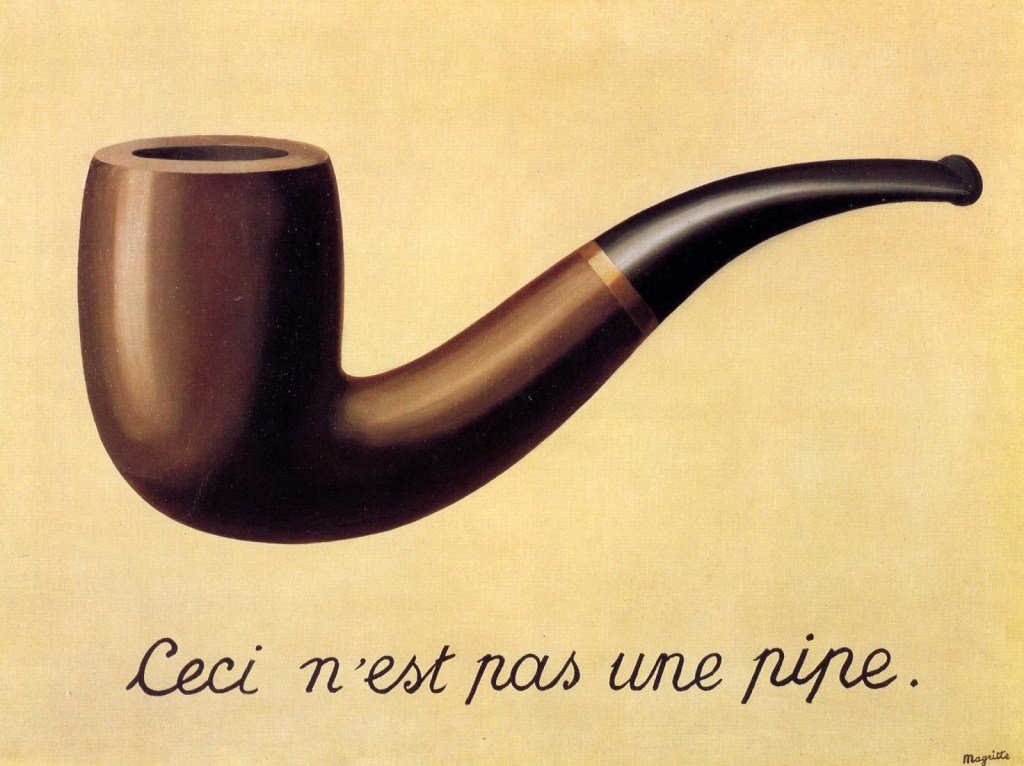

Magritte’s pipe enters precisely here, as an interruption and a reminder.

His famous declaration is at once a clever joke at the viewer’s expense and a philosophical prod: a pipe painted on canvas is not a pipe, and neither is the word “pipe” nor the concept we carry in our minds. Each belongs to a different layer of meaning.

And yet, the very act of calling something not a pipe continues to carry the constraint it claims to lift.

Before a craftsperson ever touches briar, before a designer ever drills a draft hole or shapes a stem, the category “pipe” has already narrowed the imaginative landscape. The moment we name something, we inherit a set of expectations that may be functional, cultural, anatomical or conceptual. Creativity is not a free field but a negotiation with meanings that predate us.

This is what non-representational artists tried to outrun. They suspected that as long as the work depicted something, it remained tethered to inherited meaning. Their rebellion was essentially metaphysical:

- Can one create without participating in meaning-making?

- Or is meaning itself the unavoidable residue of any creative act?

What Magritte forces us to confront is not the constraint of naming but the constraint of un-naming. What does the refusal to let an image settle into the category it so obviously inhabits convey? Declaring that something is not a pipe generates its own boundaries. It destabilizes meaning, but it also creates a new frame through which the viewer must proceed. And this is where the meditation begins: creativity doesn’t arise in a vacuum but in a terrain already shaped by decisions we didn’t make.

This is why the first utterance in human history could never have detonated a fully formed cosmos of meaning. Meaning did not, and arguably cannot, burst forth complete. It accreted over time. Sedimented. Layer by layer, each new association adhering to earlier ones, thickening the conceptual mass. Meaning grows the way river deltas do: through deposits, through confluences, through slow accumulation until a shape emerges.

This accretive nature is one of meaning’s most curious features. As detail increases, meanings proliferate. As associations multiply, the sense of “what something is” deepens.

But does this expansion of associations necessarily advance understanding?

In one sense, yes, by definition, the more relational threads a mind can weave around a thing, the richer the mental model becomes. We understand more of something when we can link it to more contexts, more analogies, more histories.

Yet this is the shallow, quantitative reading of understanding. The maximalist sense, the kind that grasps essence rather than adjacency, works differently.

We can drown in associations. We can mistake the proliferation of one-to-many associations for insight. We can fill a page with notes and miss the argument. We can trace every branch and never see the tree.

The forest/trees tension is not a cliché here, it is a structural feature of meaning itself. Meaning expands outward, but understanding contracts toward coherence. Meaning is centrifugal; understanding is centripetal. Creativity, then, lives in the interplay between the widening field of associations and the narrowing search for shape.

This tension becomes especially vivid when we turn to instruments. Pipes, pens, watches, cameras. These all exist at the intersection of immense accumulated meaning and the singularity of purpose. A sea of possibilities, some realized, others latent, surrounds any implement, yet the maker must still bring the object back to functional coherence. You cannot erase the accumulated delta of meaning and conjure something wholly new; if it no longer fulfills its purpose, it ceases to be the thing it claims to be. And if it does fulfill its purpose, it inevitably inherits the meaning that comes with the category.

In that sense, instruments are tiny laboratories for navigating meaning itself. They remind us how much we inherit and how little we can reinvent at once. They show us how creativity requires a steady hand on the dial between too much association and too little. They reveal how understanding emerges not just from adding details but from knowing which details to ignore.

This is why the persistent forms, billiard, bulldog, Dublin, feel almost preordained. They stand as the settled solutions of countless negotiations between expanding meaning and focused understanding. They are where accreted meaning meets embodied use.

The question gets knotty quickly. Is all creativity a form of meaning-making? It depends who is deemed the maker of that meaning. One can produce a gesture, a mark, a shape with no intended significance. But the world refuses to leave these naked signs untouched. Viewers will impose meaning even if the maker does not. Conversely, not all meaning-making feels creative. Bureaucracies generate meaning constantly, but few would call their memos creative.

Perhaps the entanglement is asymmetric:

- Creativity usually produces meaning, even when it tries not to.

- Meaning-making is not necessarily creative, yet it shapes the environment in which creativity unfolds.

This tension becomes interesting when we shift focus from fine art to instruments. Fine art often aspires to be an intellectual exercise: a confrontation, a puzzle, a philosophical provocation. Creative expression moves outward from concept to form. Whether the paint or clay becomes useful is irrelevant; the craft is subordinate to the idea.

Instrument-making reverses the polarity. Here, creative expression grows out of constraint. The instrument must function. It must satisfy the hand, the mouth, the eye. It must obey airflow, friction, gravity, ergonomics. Artistry emerges in the refinement of structure, the honoring of purpose. In a sense, instrument-makers are philosophers who work in wood and metal rather than in abstraction.

Both are creative. Both are meaning-making. But their relationship to meaning is different:

- Fine art interrogates meaning.

- Instruments stabilize meaning by participating in repeatable forms.

What, then, of instruments made without aesthetic intent? The disposable ballpoint. The stamped metal wristwatch of a worker. The mass-produced pipe smoked in a corner shop. These objects were not birthed through a creative act, but someone, eventually, will find beauty in them. A collector admires the patina. A photographer revels in the geometry. A writer draws meaning from the very indifference of their birth.

So what can we say about unintended aesthetics?

Every choice can become an aesthetic choice once viewed by someone who cares. Even the omission of intention is a kind of style. Even utility has a silhouette. Even standardization has a texture that can be admired.

Designers sometimes stumble into elegance. Craftsmen sometimes achieve beauty while chasing only durability. We, the interpreters, complete the aesthetic circuit.

Let’s add another layer. There is a sense in which all meaning making is communication and all communication is meaning making. Push the terms far enough and they begin to overlap or bleed into each other. Any signal that alters another mind’s state, intentionally or not, participates in both. But this overlap is unstable. It shimmers rather than radiates.

Take the barking dog.

The dog communicates. It wants to go out. It has learned that a certain sound, emitted with a certain insistence, produces a certain human response. There is a kind of intention there, a directedness. But does the dog mean anything in the way humans mean things? Does it understand its bark as a symbol, as a unit in a broader system of signification? Or is the bark merely a behavior that has, through repetition and reinforcement, been yoked to a predictable stimulus?

Here the symmetry collapses:

- It is communication.

- It is not meaning-making; at least not from the dog’s standpoint.

The meaning-making happens on the human end, through our interpretive machinery. We receive the signal, contextualize it, convert it into a functional understanding: the dog needs to go out. The meaning is the product of our cognitive labor, not the dog’s conceptual intent.

When a dog barks at another dog, we don’t say they are “discussing” anything. They are not exchanging propositions. They are triggering and responding to stimuli within a behavioral ecology. The structure is closer to a dance than a dialogue.

Perhaps meaning-making is not inherent in the signal but in the interpreter.

A signal becomes meaning only when something capable of meaning receives it.

The inconsistency chafes because we habitually conflate meaning with communication. We mistake their partial overlap for identity. But the distinction is important: meaning requires a grasp (however implicit) of a system of relations, of this standing for that, of this gesture or sound existing within a broader field of possible gestures and sounds.

A dog does not, as far as we know, operate within a symbolic horizon in this way. Humans do, and perhaps cannot avoid doing so.

One might argue that these apparent inconsistencies are artifacts of language; that our vocabulary for communication and meaning was developed for human cognition and thus bends awkwardly when stretched over other species. The dog is not confused; our categories are. We are asking our language to map a terrain it was not evolved to describe.

But it is not obvious that this is merely a linguistic glitch. Our language reflects distinctions that exist in the structure of cognition itself: between symbolic representation and mere signaling; between choosing to mean and triggering a reaction; and between constructing significance and participating in a feedback loop.

If language strains here, it may be because the phenomena are genuinely layered, not because our words are inadequate. The distance between communication and meaning-making may not be a flaw in vocabulary but a feature of the world.

And this brings us back, subtly, but inevitably, to our meditation on instruments.

Instruments are designed for creatures capable of meaning. A pipe is not just a smoking apparatus; it is a participant in a symbolic ecology of forms, traditions, categories, uses. A dog cannot make a pipe because a dog cannot intend a form to mean anything beyond its immediate utility. Humans, by contrast, cannot not make meaning. Even when we pursue pure function, we end up generating structures others will someday interpret aesthetically or symbolically.

We are meaning-making organisms, even when we don’t mean to be.

Consider the crow or the chimp. Both can use sticks or stones to get at food. They recognize function. They solve problems. They understand, at some tacit level, that a stick too short for the task must be replaced by a longer one. There is intention here. There is evaluation. But their relationship to the tool is immediate and evanescent.

They do not store a small arsenal of sticks of varying lengths for later use. They do not shape or refine the sticks. They do not commit to a future in which this tool will matter again.

The tool is a momentary extension of the body, nothing more.

This is where the first line between animal and human opens. The moment we intend a tool to be used again – when it stops being temporary and becomes future-facing – it begins to transform into an instrument.

The future is the crucible of creativity.

A tool used once can remain crude. An instrument meant for repeated use acquires refinement.

And refinement, even when pursued only for functional reasons, smoother grip, straighter shaft, more durable material, inevitably generates aesthetic qualities. A better tool looks better, feels better, embodies a kind of rightness. Even if the maker intends nothing aesthetic, the observer cannot help but evaluate it aesthetically.

The aesthetic dimension arises not from the maker’s deliberate intent but from the observer’s capacity to perceive patterns, harmony, proportion, elegance; qualities that piggyback on function.

In this sense, the aesthetic state of an object is not fixed at the moment of its making. It exists in something like a quantum haze: a cloud of potential readings, unused, uncollapsed, until a viewer encounters it.

A pipe is built to smoke. A nib is built to write. A watch is built to tell time.

But each of them carries, latent within its structure, aesthetic possibilities. Its beauty, or lack thereof, is indeterminate until someone looks, touches, measures, or contemplates it.

The observer collapses the aesthetic waveform.

The maker may have sharpened the stem angle for airflow, not for beauty. The briar may have been chosen initially for durability, not its flame or bird’s eye pattern. The taper of the shank may have been dictated by mechanics, not harmony.

But when the human eye rests upon the instrument, when the hand feels its balance, when the mind perceives coherence in its shape, the aesthetic meaning resolves.

In the end, a pipe is not simply a pipe, and an instrument is never merely what it does. It is a mirror reflecting back the strange condition of beings who cannot help but turn use into symbol, function into form, signal into meaning.

We carve briar and shape stems, but what we are really shaping is the boundary between the world as it is and the world as we can imagine it.

Every instrument is a small treaty between these two domains. A site where matter yields to mind, and mind yields to the inherited categories it did not choose.

And so, the meditation lands here: we are creatures who inhabit a universe saturated with our own creations, yet continually surprised by the meanings they return to us.

Instruments do not just extend our capacities; they reveal, through their perpetual evolution, the bottomless depth of our creative nature.